S&P 500 is ‘expensive’, there’s no way to sugar coat it, Bank of America’s Savita Subramanian

The S&P 500 is statistically expensive on 18 of 20 metrics Subramanian tracks, and it has never been more expensive on market cap to GDP, price to book, price to operating cash flow and enterprise value to sales.

Subramanian said metrics reflect in part that “today’s S&P is higher quality, more asset light, less levered” among other realities and so historical comparisons are problematic.

Still, there are lessons for investors given where the index’s sectors are concerned.

“Our momentum and value model now ranks health care as number one and real estate as number three – and we are overweight both sectors in our US strategy work, intended for investors with a medium term (about 12 months) outlook,” Subramanian said in a note.

As for tech, Bofa is market-weight, which is number two this month, she said.

“Health care and real estate are inexpensive relative to historical market multiples. More importantly, the sectors are cheap for good reasons: positive trends in revisions compared to the broader market, plus a three-month run of outperformance. These factors in concert indicate good value.

“On the flipside, Consumer Staples, which we are also overweight in our strategy work, may be less likely to rally in the near-term as it screens as a ‘value trap’ – cheap only because its relative price has fallen faster than analysts have cut earnings estimates.”

I've been thinking lately about the global Macro situation and thought it was worth putting some thoughts on paper to see what the Strawman community thinks.

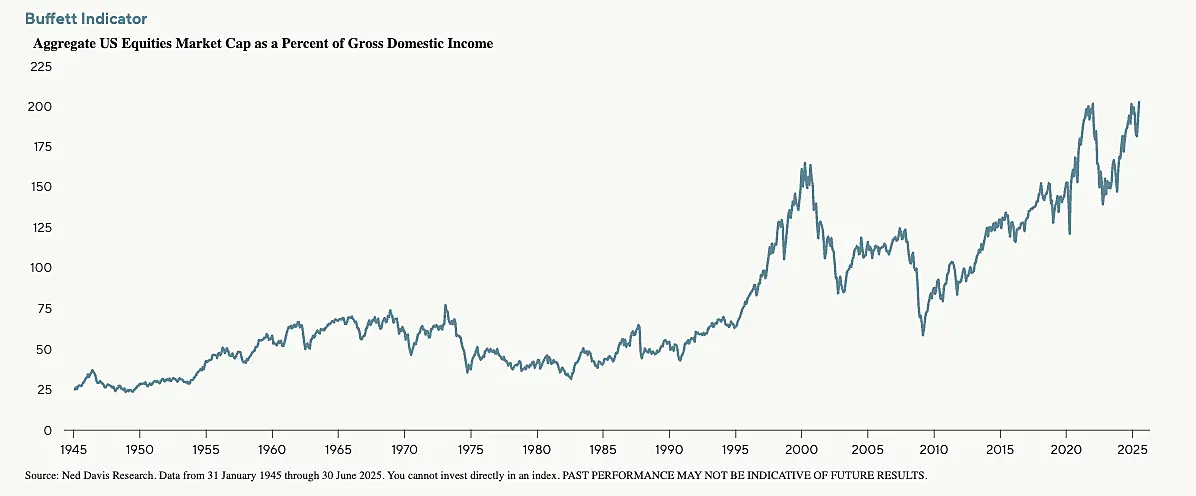

The first detail was this graph shared by LiveWire today showing that the Buffett Indicator - the ratio of US stock market value to GDP- now sits higher than at the dotcom peak.

The second detail was a fantastic article written by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard in the Telegraph and reproduced in the Fairfax papers today. The key sections that I found fascinating are below. You can read the full article here - https://www.theage.com.au/business/the-economy/trump-s-war-on-the-world-is-starting-to-unleash-pain-20250811-p5mluk.html

"We have since learnt that US jobs growth ground to a screeching halt in May and June, just as labour economists had predicted. The picture has been getting slowly worse ever since.

The ISM manufacturing index is sliding into deeper contraction. The services index is catching up with a lag, hovering on the boom-bust line of 50. The employment sub-index for both is now at recessionary levels – the “redneck recession” for poor people, as the ever-irreverent Drudge Report calls it.

“Most key metrics that we track suggest labour demand is at its lowest point since the pandemic,” said Citigroup’s US economist Veronica Clark.

For now, it is a story of “low hiring”. It becomes dangerous if companies start firing as well. That can turn into a self-feeding downward spiral of mass layoffs that slips control, forcing the Fed to slash rates to the bone.

Wall Street has shrugged off the slowdown, but that is because traders are betting on the “Fed put” – Vickie Chang, from Goldman Sachs, says markets have priced in both a “negative US growth shock” and a “doveish policy shock” at the same time.

The two more or less offset each other. In other words, the Fed will ensure that the Schiller price-to-earnings ratio on Wall Street remains near the peak of the dotcom bubble at over 38, and junk bond spreads remain as compressed as they were at the peak of the Lehman credit bubble. Uncle Jerome will keep investors fat and happy.

The Fed will undoubtedly cut rates, but it is an invidious position. The next shocker may well be the core inflation figures out next week. The delayed effects of the tariffs are about to feed through with malicious and unstoppable force. Welcome to 1970s Nixonian stagflation. Donald Trump will doubtless declare that the index has been manipulated by Marxist fifth columnists. Good luck with that.

The US is unable to substitute 90 per cent of its current imports with local production. Trump’s trade taxes will be paid by US consumers via higher prices, and by US companies with plants abroad or reliance on foreign inputs via lower profit margins.

Caterpillar has already warned that the Trump levy will cost it up to $US1.5 billion ($2.3 billion) a year. Brewer Molson Coors expects earnings to fall by 7 to 10 per cent because Trump’s 50 per cent tariffs on aluminium have pushed metal can costs through the roof.

We know from early warning signals – both the ISM’s service price paid index and S&P Global’s composite PMI output prices – that price impulse is filtering through with the usual multi-month lag, and that headline inflation will approach an annualised rate near 5 per cent over the next three months.

So 'live' inflation is estimated to be at 5%. The labour market is at its weakest point since the pandemic. Major listed US companies are expecting significant margin contraction and earnings reductions. And somehow we're led to believe that the US share markets that lead the world are correctly at their highest valuations ever?

I honestly feel like I'm missing something obvious here. No emergency rate cuts that have been priced in will save the US economy from contracting here will they?

And more importantly for the straw community. If this is a view I hold, but it is widely agreed that attempting to time the market is a mugs game. How does an intelligent investor respond with our portfolios?

I didn't realise this was the case, but AFR is reporting that

"Analysts expect company earnings on the ASX to fall about 1 per cent in the 2025 financial year – the third straight year of contraction."

So, profits (in aggregate) have been dropping for 3 years, during which the index has risen to record highs. The obvious implications of which are:

"The ASX All Industrials Index (which excludes resources) trades at a record forward price-to-earnings multiple of 21.7 times."

I share this not so much to be bearish, but only to suggest that now as much as ever is a good time to be selective with your investments. There's always pockets of value, and in fact the same article says that 4 of the 11 sectors on the ASX are trading below their 5 year average PE multiple (basically tech and financials are the main ones pushing up the total market multiple).

I've always hated the term "it's a stock pickers market", but that actually rings true right now.

All that being said, if we see monetary conditions continue to ease (which seems to be the consensus), and the fiscal side of things keep pumping, well, I wouldn't be surprised to see the market multiple keep rising. Things can remain irrational for a long time (*cough* CBA *cough*).

Who knows? I wouldn't try and trade around all this. But if you're holding something that's trading at a lofty multiple, just be sure it's got the quality and growth potential to justify it.