More from Alex Turnbull here: (from his substack, the guy is switched on!): https://syncretica.substack.com/p/portfolio-theory-and-trade

Sample:

As some readers may know I have been otherwise engaged on some work with Employ America regarding critical minerals and have had less time to post. That being said, a recent exchange on twitter has inspired me to sketch out a stylized model of trade and geopolitical risk that leads to supply chain reconfigurations.

There are two types of goods that I will deal with here.

Commodities or Near Commodities

Commodities that are either entries on the periodic table or close to it - metals, coal, oil, gas and bulk grains. For these goods that are bulky and relatively low dollar value per tonne the logistics matters: coal sitting on the other side of the world that comes out of the ground in Xinjiang for $20 per tonne may be cheap there, but it is ~$200 delivered to the US East Coast. Relations matter, topology matters, and modeling these markets without taking account of transport is not worth the time or of much value. It is especially so if that transport can be interrupted by conflict. Not much coking coal has made it out of the Donbas recently, and for some time in 2022 not much wheat was being exported either. The stylized facts for these products are:

- The world seldom runs out of the product or experiences a “molecule crisis”.

- The world is regularly hit by logistical crises where products get stranded until they are resolved. Some of these are geopolitical but many are climatological.

- US LNG export capacity constraints, Manganese export ports hit in storms, the list goes on and will continue. There is usually capacity somewhere, just not where you need it.

Geopolitics’ impact on these markets can be in the form of outright conflict shuttering assets due to fighting, or logistical constraints. Logistical constraints tend to matter more as has been the case in the Ukraine conflict. Explicitly modeling who faces what costs in the face of various probable logistical shocks is what defines a frontier of risk versus reward. Countries may face local price crashes or rallies due to these broken edges on the graph instead of facing a uniform energy shock. A modeler can then extend this to multiple periods where shocks may be resolved or not and then optimize ex ante for how their energy system or agriculture should be. For grains you might run bigger stockpiles, for energy imports you might decarbonize faster after internalizing costs both in terms of carbon and trade flow risks that can be interrupted by unfriendly parties. In summary:

- Build the edges and nodes and business as usual flows which are close to optimal.

- Run some shocks, reoptimize to see where the chips fall.

- Evaluate costs.

- Probabilistically weigh the scenarios and evaluate what “hedging” looks like and costs.

- Hedging is usually some combination of buffer stocks, domestic production or substitution.

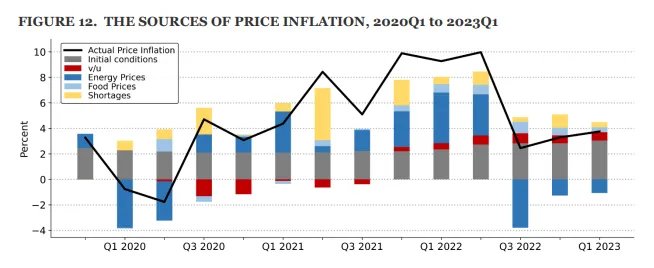

- Optimize away for your degree of risk aversion, or, consider what downstream impacts of this particular supply shock are on monetary policy along the lines of Isabella Weber or Bernanke and Blanchard and then integrate it into your monetary policy function and likely fiscal costs. Easy (not really).

A few stylized facts from such a model:

- There is a positive feedback loop from geopolitical risk to trade integration and high path dependence. The higher the perception of risk the less integration. Note this approach considers costs of transition from current BAU flows and does not represent an abstract “what if we started from a blank sheet of paper”. Initial moves may be limited and involve substantial third country routing and integration but get fairly non-linear in my modeling on coal.

- The shocks hedged are very specific. Barring a move to full Juche - North Korean style - you hedge specific scenarios where edges on the trade graph cease to exist or experience vastly higher costs. A South China Sea or East China Sea blockade is modelable and something to consider, the coral colonies and marine wildlife of the Great Barrier Reef rising up against the Queensland coal sector is not.

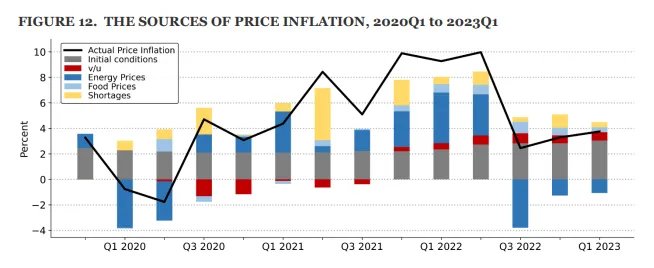

Most of my work has focussed on energy and coal heavily drawing upon the PY-PSA community and various efforts early on in the Ukraine shock to evaluate Europe’s gas adequacy by Bruegel. For energy security the simple answer is “decarbonize faster” and “store more liquids until you have enough EVs”. Additional measures might include more LNG terminals and takeaway capacity to ensure no excessive reliance on particular countries (Russia, Qatar) or the shipping channels they use to export (Red Sea). The monetary impact is the excess inflation explained by the “energy prices” bars in the graph from the Bernanke and Blanchard paper below:

Food price impacts are smaller and were similarly logistical in nature - wheat prices in 2022 collapsed in Ukraine due to lack of takeaway capacity and soared elsewhere. Larger buffer stocks are the only realistic solution here because while you could readily put solar in Egypt or Kenya you cannot force wheat to grow in a climate or soil it cannot.

Energy security and this analysis also should take account of embedded or indirect energy - the energy that goes into other products that are traded. Jun Ukita Shepard’s PhD thesis and work with her advisor Lincoln Pratson are excellent in that they take account of this deeper dependence and risk as well as the logistical issues around trade, particularly maritime trade. Their excellent Nature Article “The Myth of US Energy Independence” outlines some of these deep dependencies that emerged in 2022 in energy intensive goods like fertilizers, aluminum and the like and outlines three approaches to deal with these risks of “Buy American” (consuming less or substituting), “Made in America” (producing more domestically) which is constrained by the US resource endowment and investing in energy security abroad both fossil and renewable. An excellent paragraph below on vehicles outlines the general approach:

What does this all mean? First, the US should not only manufacture key commodities domestically, but also invest in building out their associated supply chains. This means for instance that if General Motors invests US$7 billion in electric vehicle manufacturing in Michigan22, policymakers should make sure that inputs into those vehicles, including subcomponents and refined materials, can be produced domestically as well. Where it is not possible to source materials domestically, policymakers should invest in innovative designs for alternative technologies while securing imports of these key inputs. And to secure these imports, the US should invest in the energy independence of manufacturing economies. This includes independence from US oil and gas and points to clean energy systems. By rapidly establishing and strengthening domestic clean energy supply chains, the US can not only increase its competitiveness in global markets but promote global energy security by diversifying the world’s indirect energy portfolio.

Building more functional and coherent hedging and contracting markets for critical minerals - something I have spent some time on lately - is an important part of this. Properly accounting for this embedded energy is something Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms do well and the data flow from those being introduced might provide the material to make this kind of analysis more routine.

Manufactured Goods

The “shortages” component of the inflation shock in the Bernanke and Blanchard paper is more complicated because while a tonne of coal is readily substituted with another tonne of coal of similar properties the same does not apply to semiconductors. The acute surge in manufactured goods inflation in 2021 was to a great extent made in Malaysia - because that is where COVID was blowing up at the time and where chip packaging and testing was concentrated, especially for autos which in turn led to auto supply shortages. Geographical flows matter in some manufactured goods more than others but flows through production steps are crucial and this criticality varies at different levels of the supply chain. Chips are value dense enough that they might be shipped by air and often are but that option is not available for autos. For autos upstream matters, but so does whether you can move car carriers around which you generally cannot in a conflict.

While I have not done detailed academic analysis of the directed flow of components in supply chains for autos, for example, there are a few stylized facts here.

- Excess concentration in any one step is a significant vulnerability. Moves by manufacturers to have a “China plus one” footprint are common because you get a lot from a little diversification at each production step by eliminating choke points.

- There are generally limits to agglomeration economics and scale economies for plants. Having multiple hubs makes sense so long as they are not subscale and otherwise well connected. Analog semiconductor expansions in the US and Europe post COVID are quite clearly a response to this and from company calls so long as the market is above a particular size then it makes sense.

- Some projects are inherently “zero or one” with very large minimum ticket sizes like leading edge semiconductor fabs. The CHIPS act specifically solves this flaw of having so much natural agglomeration that you get excessive supply chain risk which nobody but a government can pay to fix.

So how best to analyze the risk here?

- Recursive search for dependencies (market share) on country X in product Y. You can just have a flat weight of full trade breakdown with country X, or in specific products Y from country X. Iterate through X and Y. Perhaps even better is looking at clusters of “friendly” and “less friendly” and “neutral” and looking at aggregated dependencies between these. This does not uncover every potential ruction like Japan and Korea’s brief chemical dispute but should capture the most important ones.

- Evaluate substitutability of suppliers which may be easier for some things than others.

- Look at shortfalls and risk both at the product and downstream level.

This kind of input-output approach has been attempted in broad terms by Gerard DiPoppo at Bloomberg Economics and CSIS but does not thus far take account of all US and EU investments in chip fabs and capacity which is where Bloomberg Economics saw the greatest issues with trade dependencies on China. An update might be worthwhile at some point.

China clearly has done this analysis as it tries to slow US semiconductor decoupling in subtle ways. Building new lines in chip fabs can be done relatively quickly, building new chemical or material supplies less so. For example, China’s recent bans on Germanium and Gallium exports hit at a weak point in US DoD supply chains and electronics. Similar export bans on graphite are targeted to slow the development of onshore battery production capacity in the US. It would be desirable for other countries to know where the hits are likely to come before by doing a rigorous analysis of exposures in manufacturing supply chains, especially things that are inherently hard to scale up quickly like mines or other things on the periodic table which require lengthy environmental approvals.

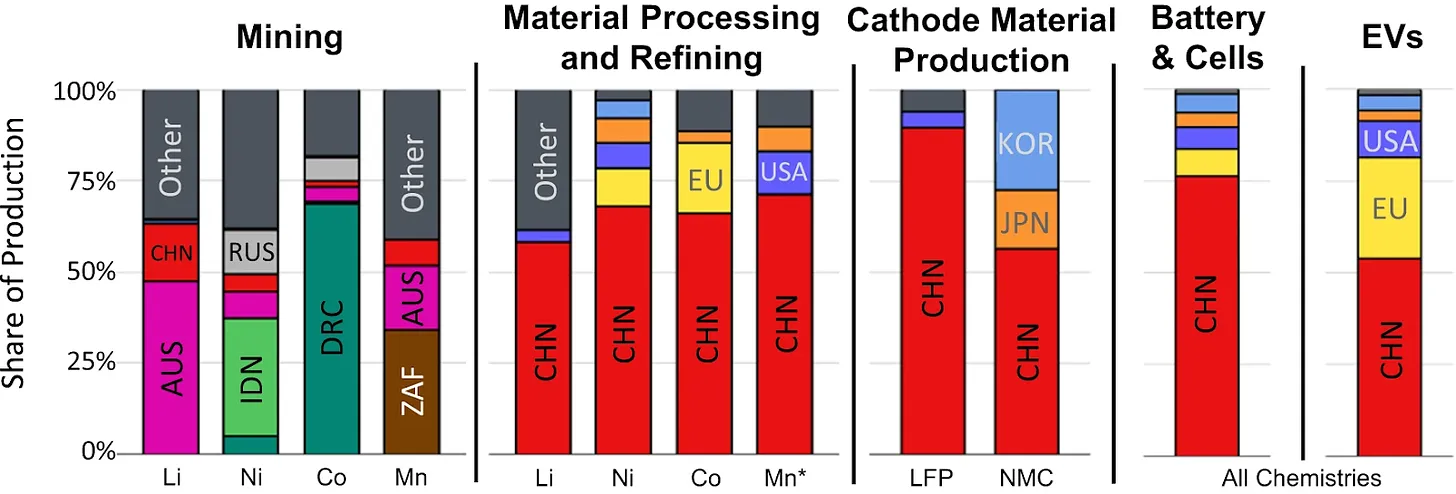

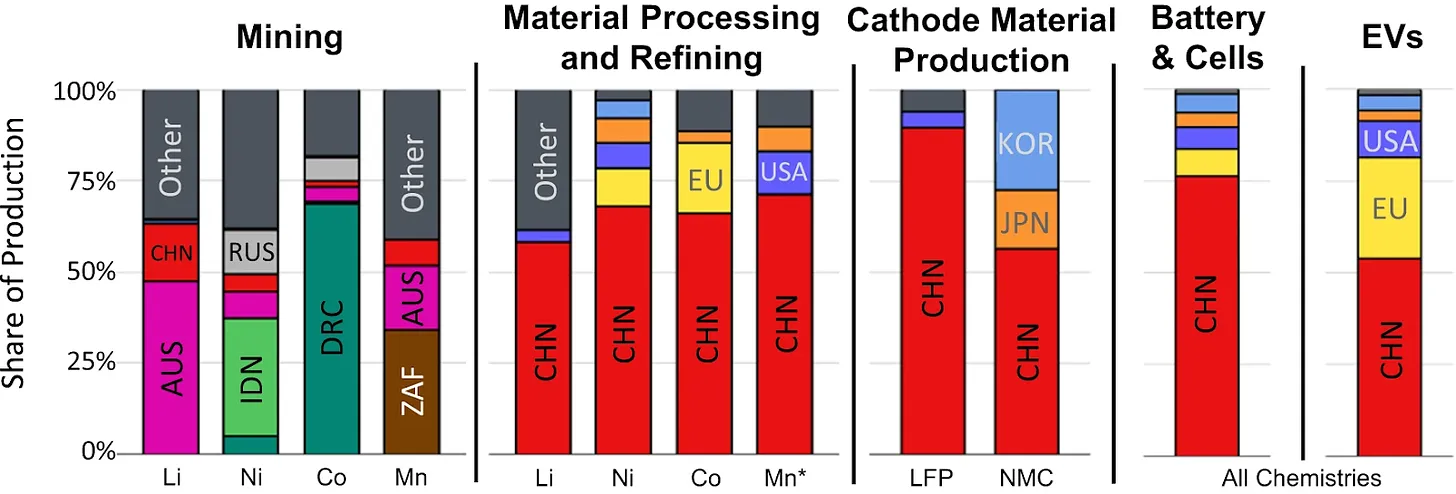

To that end dealing with battery supply chains is going to be hard but not insurmountable. The image below from Cheng, Fuchs et al’s paper shows that China is not that big in mining but in material processing and refining and cathode materials. An industry China built quickly can likely be replicated elsewhere - winning geology cannot. Until that is done though the level of vulnerability is very high.

One weak point in US policy is that while it is doing a phenomenal job of filling gaps in semiconductors and onshore capacity in batteries, solar and the like it does not have a good interface for dealing with partner countries on certain products the US does not have a natural endowment in. Some of this is due to lending mandates being required to stay in country, some of this is just politics. The EA work is intended to make US exchanges and trading central to this new trade topology in critical minerals outside of China. This is desirable for the US but also allows diversification for countries that are currently very dependent on China for processing, and which do not have large domestic markets to stand up downstream capacity.

So apologies for being a little quiet but there is work to do.

--- end of sample ---

If that stuff is up your alley - have a look at the MoM poddy yesterday:

[Click on Matty's left eyebrow to view that MoM podcast]