Fears over the impact of the worsening coronavirus outbreak continue to drive global markets sharply lower. And, potentially, things could get a lot worse from here.

For the long term investor, it’s easy to deride such moves as mere ‘speed-bumps’ along an otherwise sure and prosperous road. Insert a Buffett quote, add a long term chart of market growth and carry on with a stiff upper lip.

All that’s reasonable, of course, but it’s not an excuse to ignore current events and market valuations. Even investors with the longest of time frames should sometimes adopt a cautious stance (as it appears Mr Buffett himself is at the moment, given Berkshire’s cash holdings and lack of major investments in recent times).

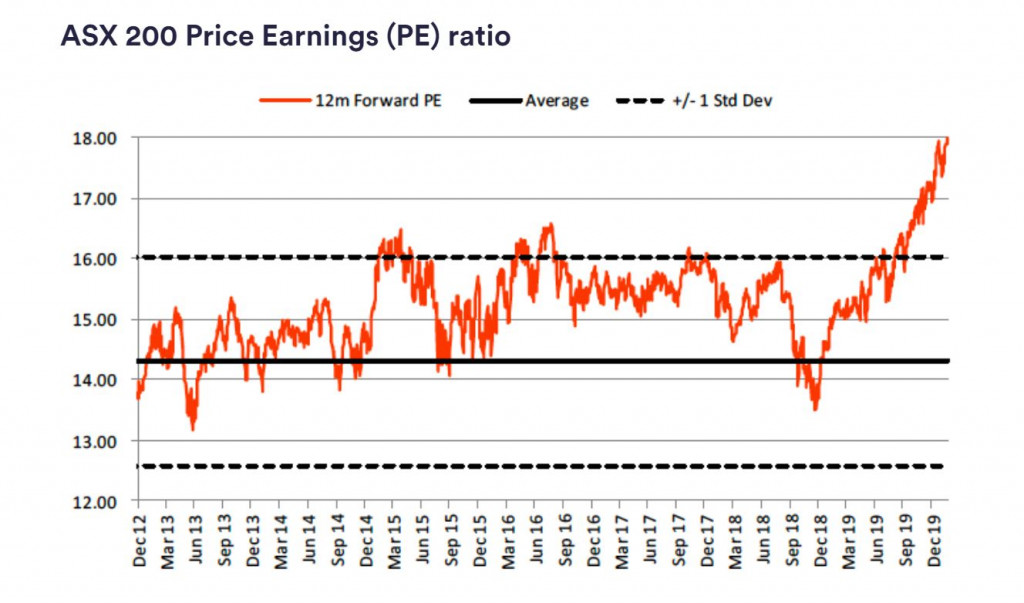

One reason for caution is the current elevated valuations of the market. The price-to-earnings (PE) ratio for the ASX200, based on 12 month forecast earnings, is at levels not seen for a long time.

That’s not necessarily a sign of imminent doom. Earnings may rise faster than expected, interest rates could fall and remain depressed for longer than imagined, or the irrationality (if that’s what it is) could simply last a lot longer than we might sensibly expect.

The timing of any ‘reversion to the mean’ here is a fool’s errand, but what this chart reveals is that, rightly or wrongly, investors are very optimistic towards the future. The question is whether (all else being equal) the coronavirus outbreak should change that.

Real World Impact

Beyond the hit to sentiment, and the tragic human suffering, the virus will most certainly have a material impact on economic activity.

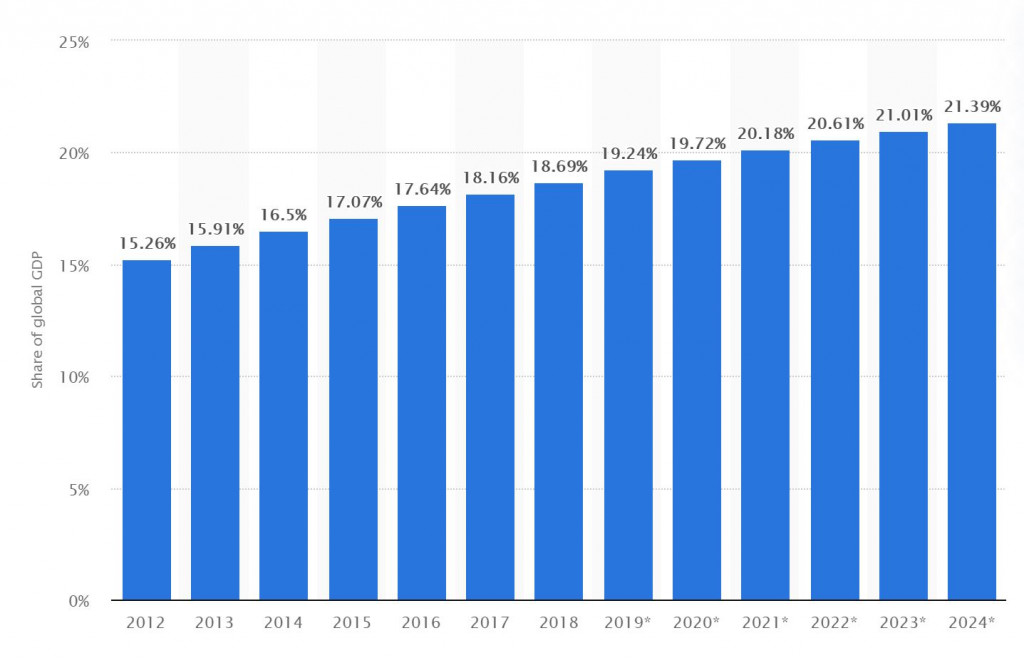

China, the epicenter of the pandemic, is the world’s second largest economy and accounts for almost 20% of global GDP (adjusted for purchasing power parity). It’s also the ‘world’s factory’, accounting for 13% of global trade.

Source: Statista

According to a recent Reuters poll of economists, China’s economic growth is expected to slow to 4.5% in the first quarter of 2020, down from 6% in the previous quarter and the slowest pace of growth since the GFC.

Australia is especially sensitive to China’s economy, given it is a major customer for our three largest exports — iron ore, coal and education. One third of all our exports go to the Middle Kingdom.

With 1.5 million Chinese visiting Australia each year, the tourism industry is also keenly exposed. But the potential impact is much wider and will include any company that relies on Chinese manufactured goods (e.g. JB Hi Fi said recently that a supply shortage would be evident in the coming month or so).

Aside from lost sales, there’s also potential inflationary effects as the supply of goods continues to dry up. Indeed, China’s CPI was 5.4% in January, more than double the average over preceding years, driven by a sharp surge in food prices.

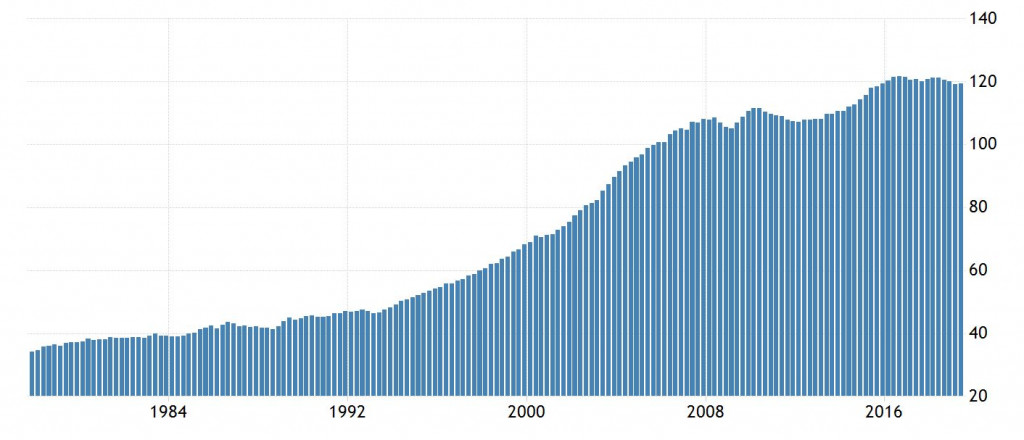

None of this is encouraging, but what’s especially worrying is that the world is facing this challenge carrying record amounts of debt. According to the World Bank, global debt is around 230% of GDP — a record high. Australia’s household sector is also very leveraged, at around 120% of GDP.

Source: Tradingeconomics.com

Given all this, it’s difficult to label the market’s reaction to the unfolding crisis as irrational. Especially given the potential for things to get worse — maybe a lot worse — before they get better. And that’s the problem, not even the experts can say exactly how this will play out. It’s simply too early to tell; we don’t have sufficient data and there are a host of variables at play.

What to do?

In these situations, it’s tempting just to sell out and wait for more certainty. The trouble is, as history unequivocally shows, most risks don’t eventuate, at least not to the degree that many initially fear. Those that jump at every shadow tend to do very poorly, even if their fears are occasionally vindicated.

Plus, it assumes you’ll know when to buy back in. Good luck with that.

You could hedge your portfolio, using options or similar instruments, but here too history suggests such an approach is usually counter-productive. That being said, many gladly accept that compromise for the peace of mind it offers.

You could shift your holdings into defensive assets, such as gold. However investors likewise need some talent in timing to make this worthwhile. Such ‘flights to safety’ can reverse as quickly as they start.

Or, you could just stay the course.

Granted, that’s easier said than done, but so long as you bought well it’s usually the best approach. Even if you suffer some brutal short-term losses along the way. Whenever this thing resolves — and it will — we’ll almost certainly come to see it as a buying opportunity.

As always, a rational approach to valuation is key.

Valuing short term impacts

The value of a business is best defined as the sum total of all the cash it will generate over its useful life, appropriately discounted back to today’s dollars.

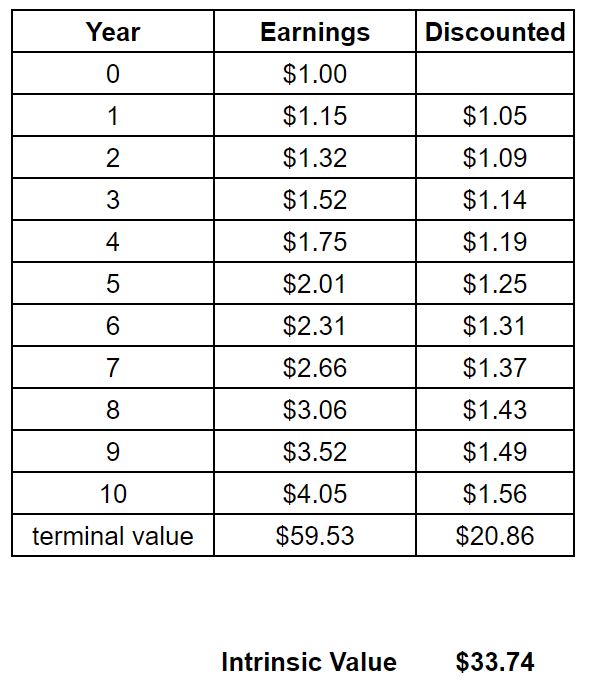

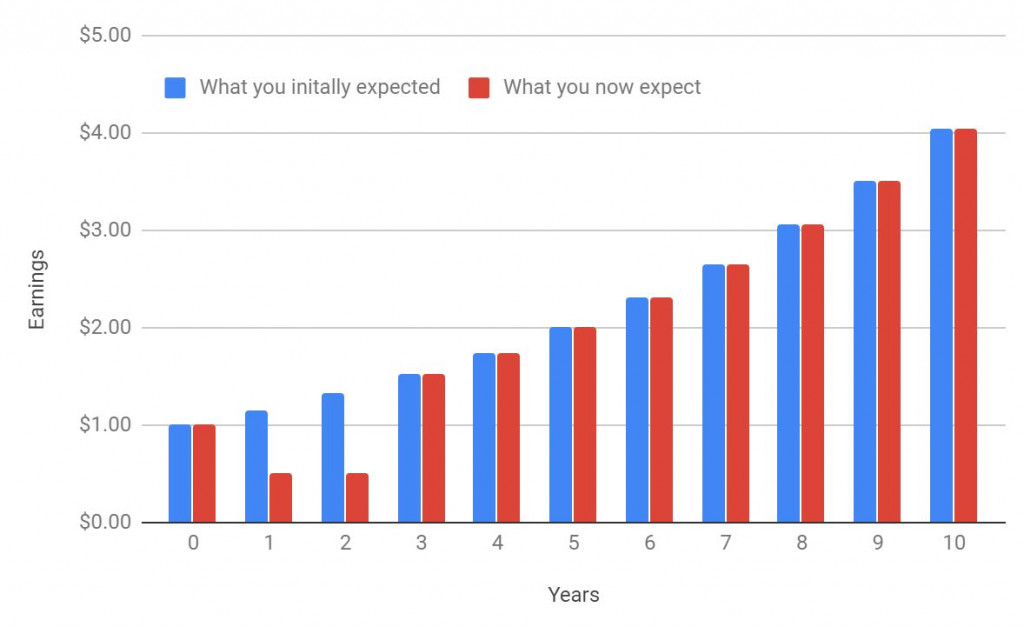

As an example, let’s consider a stock that is earning $1 per share, and is expected to grow earnings for 10 years at 15%, before hitting a terminal growth rate of 3%. Using a 10% discount rate, a standard DCF model would price our hypothetical stock at $33.74.

Now, let’s assume that the coronavirus causes our earnings expectations to fall short. In fact, let’s say that the next two years of earnings halve from the current level, before returning to our previously assumed trajectory.

When we run the same valuation model on our revised earnings, we get an intrinsic value of $32.45 — just 4% lower than our initial estimate.

Why is that? Because most of a company’s value depends on the long tail of future earnings. In our example, we modeled a harsh, but relatively short lived impact. The long-term outlook wasn’t affected at all.

Heck, even if we assume that our company will make zero profit for the next three years, before returning to our initial expectations, the calculated valuation drops just 10%.

Of course, this is a highly idealised example. Perhaps, in the real world, earnings don’t bounce back as quickly, or growth resume from the much lower base. But the point is that if the coronavirus (or any other short-term set back) doesn’t impact you earnings estimates beyond a few years, your concept of value shouldn’t really change too much.

This is also why it’s a waste of time focusing too much on near term earnings in general. In terms of sensible valuations, they only matter in regard to how they shift our expectations of longer term results.

It’s also why such dislocations can be such great buying opportunities for long-term investors.

Conclusion

If you thought a business was good value last week, and don’t expect any long-term impact from the coronavirus, your view really shouldn’t have changed that much.

If you’re highly anxious at present, it probably says a lot about your initial conviction. Those with a clear and well-reasoned investment thesis tend to be far more resilient to falling prices.

Of course, if you expect the situation to materially derail the longer term earnings profile for a company, that’s a very different story. You certainly need to rethink any investment that may require additional funding to survive.

As always, the best approach is to focus on companies with reliable earnings, strong competitive positioning, resilient balance sheets and capable and aligned managers. Further, it reminds us to be conservative in our assumptions, and factor in the inevitable nasty surprise by applying a decent margin of safety.

These are the things you CAN control. And they matter far more than futile attempts at market timing.

Strawman is Australia’s premier online investment club. Join for free to access independent & actionable recommendations from proven private investors.

Disclaimer– The author may hold positions in the stocks mentioned in this publication, at the time of writing. The information contained in the publication and the links shared are general in nature and does not take into account your personal situation. You should consider whether the information is appropriate to your needs, and where appropriate, seek professional advice from a financial adviser. For errors that warrant correction please contact the editor at admin@strawman.com.

© 2020 Strawman Pty Ltd. All rights reserved.

| Privacy Policy | Terms of Service | Financial Services Guide |

ACN: 610 908 211