Investing — be it in shares, property or emu farms — is all about value. More specifically, it’s about the identification and quantification of value.

Though that may seem a little daunting, it’s a concept that’s at the core of successful investing. Crucially, the art of valuation is something that anyone can improve on, and it’s a skill that can bring big rewards.

Frankly, if you don’t have a clear and well supported idea of value, how on Earth can you say a stock is ‘cheap’? How can you know when it’s a good time to sell? On what basis can you compare the attractiveness of the investment with other alternatives?

That’s not to say you should have super precise and complex valuation models underpinning all your investments, but without at least a general notion of a company’s true value you have no sensible touchstone with which to base your decisions.

What is value?

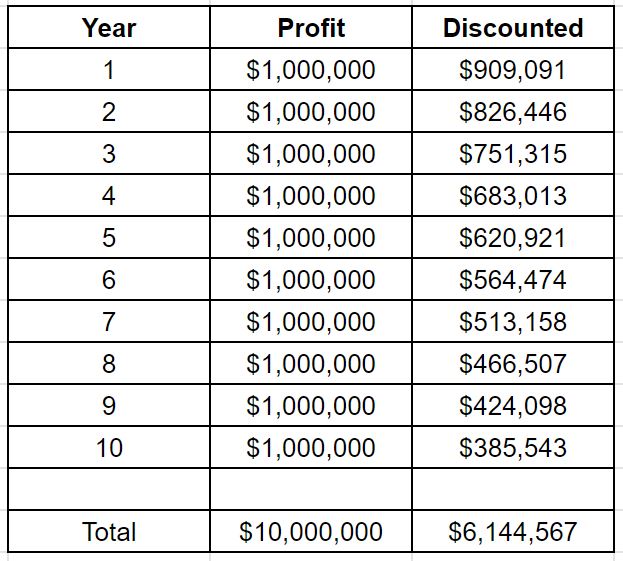

The true value of an asset is simply the sum of all the money it will ever produce for its owners. Because money in the future is worth less than money today, we also discount future cash flows to get a present value. The rate at which we discount those future earnings is determined by our desired return.

For example, if I had a company that generated exactly $1 million in net profit each year for exactly 10 years before closing down, its true value — or its intrinsic value — would be $6.14 million, assuming I wanted a 10% annual return.

The tricky thing is companies can last a lot longer than 10 years, and forecasting earnings even a few years out is notoriously difficult. You also need to consider things like inflation, interest rates and a host of other factors. To make matters worse, small differences in your assumptions can translate into big differences in the valuation.

Value may be easy to define, but it’s diabolically difficult to estimate accurately.

The good news is that we can use some generalisations to make our life easier. And, in fact, when it comes to valuations, it’s usually better to be generally right, as opposed to specifically wrong.

The humble P/E ratio

A good heuristic for value is the classic price to earnings ratio, or P/E. This is simply the price of a share divided by the per share earnings of the underlying company. Over the long-run, the market average tends to be around 16 or so, but what really makes a P/E high or low (and, hence, whether a stock is cheap or expensive) is how it compares to a company’s expected growth.

For example, a stock trading on a P/E of 50 could be incredible value if the company manages to triple its earnings in the next few years. Similarly, a P/E of 5 could represent terrible value if the business is on it’s way to obscurity.

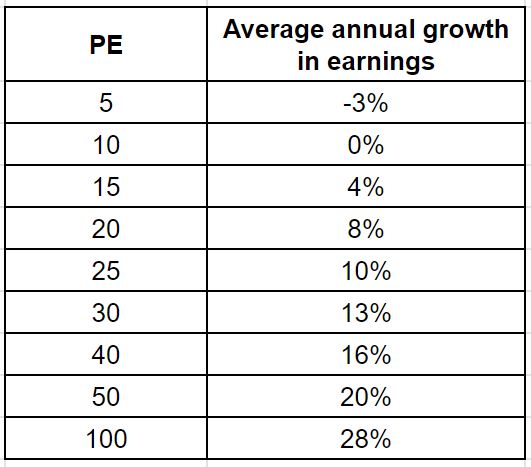

Using a basic discounted cash flow model, and some basic assumptions, we’ve crunched some numbers and produced a table that shows you the kind of growth a company needs to be able to generate over the coming decade in order justify a given P/E ratio:

It’s only a rough guide, but it helps you quickly compare the current market P/E against expectations of growth. If you think a business can sustain a 30% average annual growth in the coming decade, a current earnings multiple of 80 probably represents good value.

Bear in mind that growth rarely occurs in a straight line, risk-free rates change and ‘terminal’ growth is more a mathematical convenience than anything else. The ever changing tides of market sentiment will also ensure our neat little theoretical model won’t align perfectly with reality.

This is why a margin of safety is always a good idea. That way you’re still ok if the business falls a little short of expectations.

Example

When looking at a company’s PE, you can use this table to help determine whether the implied growth is realistic.

As an example, let’s look at Woolworths (ASX:WOW). Undoubtedly, this is a solid company with a long history of shareholder wealth creation and is likely to endure for decades to come. At present, the market is trading shares in Woolworths at a P/E of roughly 28.

If you want a 10% average annual return, you’d need to expect the business to grow it’s earnings between (roughly) 10-13% per year for the next decade. Given this very mature company has not consistently grown at that rate for many years, and consensus forecasts are calling for 5-8% annual earnings growth over the next two years, it seems difficult to make the case for value.

Not that Woolies is necessarily a bad investment — there’s a lot to be said for a reliable and relatively low risk investment, and with interest rates so low it’s not unusual for the market to demand a lower expected return. If you are happy with an average total return of ~7-8% p.a., it’s respectable.

Just don’t expect to do much better than that.

Final Thoughts

As Buffett says, price is what you pay, value is what you get.

Successful investors make all their decisions through this lens, and are able to relate an expectation of future business performance to a notion of fair value.

There are multiple ways to skin the valuation cat, and all approaches have their limitations. But by relating something as common as the P/E ratio to company earnings growth, we can easily get a better handle on a stock’s value — and ultimately make far smarter (and profitable) investment decisions.

Happy investing!

Strawman is Australia’s premier online investment club. Join for free to access independent & actionable recommendations from proven private investors.

Disclaimer– The author may hold positions in the stocks mentioned in this publication, at the time of writing. The information contained in the publication and the links shared are general in nature and does not take into account your personal situation. You should consider whether the information is appropriate to your needs, and where appropriate, seek professional advice from a financial adviser. For errors that warrant correction please contact the editor at [email protected].

© 2019 Strawman Pty Ltd. All rights reserved.

| Privacy Policy | Terms of Service | Financial Services Guide |

ACN: 610 908 211