Surprises

With a new EskyBruh due any day now the mind naturally starts to ponder the subject of change. More specifically, the concepts of surprises, lifecycles, balance and adaptation. Whilst it is a very exciting time, perhaps the biggest shock to one accustomed to viewing ‘due dates’ as ambitious aspirational deadlines is the forced re-assessment of the meaning of that phrase.

I am reminded of a trip to an iconic Australian theme park more than a decade ago. The long lines affording me the opportunity to watch the tallest ride – ‘The Giant Drop’ – go through its cycles. Its name is self-explanatory: A platform seating punters; slowly ferried along to the top of a perpendicular pole; suspended for a time atop its precipice; before a careless dropping of said platform causes the free-fall of the huddled souls harnessed to it. The sudden violence of the drop is in sharp contrast to the more parabolic motions of the roller coaster sharing the back of the tower (a difference sharp enough to cause my brother-in-law to rename that one ‘The Tower of Mild Concern’).

Like a bored Galileo sitting in a Sunday church service and watching the lamps swing [1] I timed how long the platform was held stationary at its paramount suspension. It was consistent. Around the 30 second mark from memory. When it came to my turn I was relatively forewarned and forearmed. As we were held aloft I was counting seconds and experiencing apparently less angst than some passengers who were desperately yelling to the heavens “Just let us drop already!!”, as tortured prisoners might to a particularly sadistic executioner. Then the drop came. Right on time. And it was nonetheless terrifying, only that some of sting had been taken out of the wait itself.

Yeah. A baby’s “due date” is nothing like that. Obstetricians and Mechanical Engineers are poles apart it seems. With each passing day I am experiencing more of the type of unease that was so manifest in my teenage fellow passengers on that ride.

That’s not a feeling I typically voluntarily expose myself too. I think it is natural for humans to minimise uncertainty. To control, or at least more adequately prepare for, their fate. It’s one of the reasons I love history. It reminds us that in some ways life is more predictable than we realise. Much changes, but much also doesn’t really.

Cycles

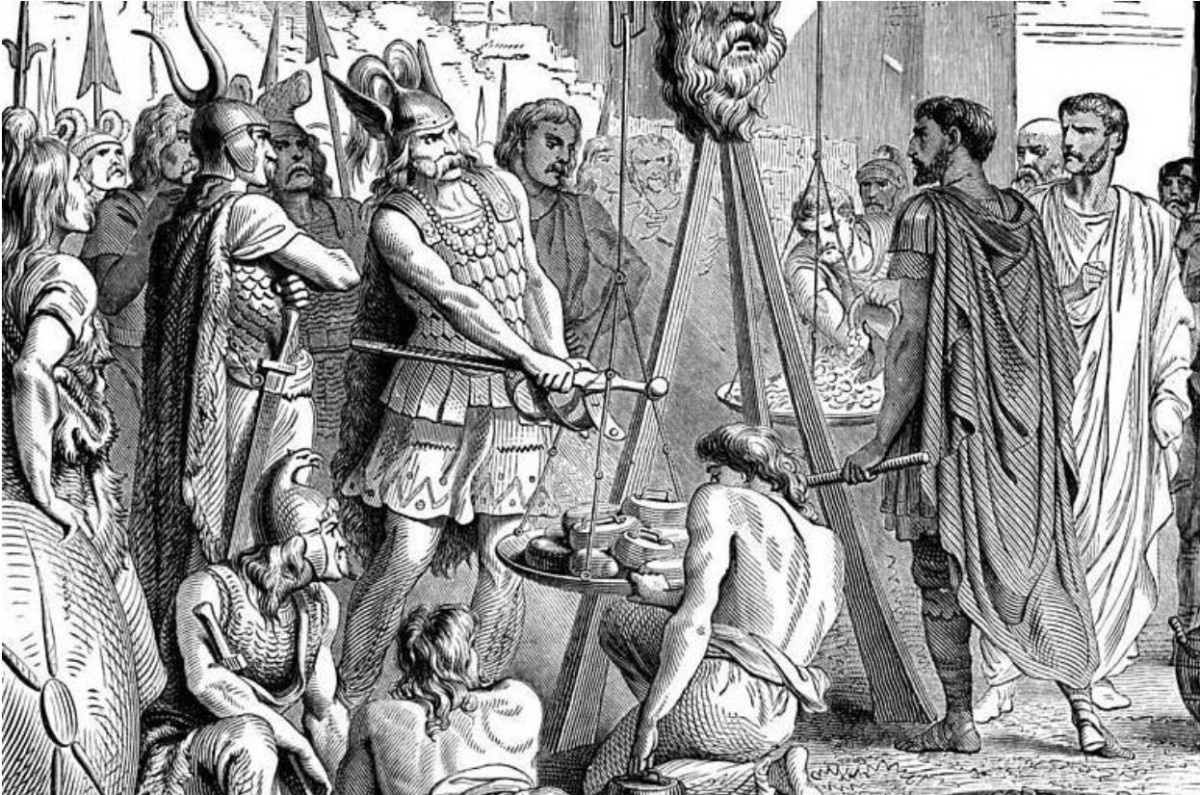

When the Gauls sacked Rome in 390 BCE it was something of a shock to the Romans [2]. The victorious Gauls subsequently levied 1000 pounds of reparations from their conquered hosts. This was long before the EU standardisation of weights and measures and predictably differences arose at settlement. An upstart Roman failed to read the atrium and thought now would be a good time to air his opinions of the Gallic scales. The Gallic chieftain Brennus briefly weighed the merits of this argument before throwing his heavy sword on the non-gold side of the scales declaring in Latin ‘Vae Victis’ – Woe to the Vanquished. A less than subtle reminder of that timeless maxim that to the victor go the spoils.

Yet even human conflict, like everything, has its patterns. Its swings and roundabouts. The Romans never forget this lesson and for the next 800 years or so they accumulated their massive empire and forced its residents (including the Gauls) to “bend the knee” before it, to borrow a Game of Thrones phrase.

“What’s this got to do with investing?” A fair question from a very patient reader.

For me the answer is because investing is also a constant cycle of re-balance and adaptation. New babies bring new changes, and not just of nappies. It becomes incumbent on you to now live longer (or at least healthier) than you may have otherwise planned. To ensure you muster your resources to obtain sufficient wealth to foster that next generation – and all whilst re-balancing the allocation of one of your most precious resources: your time.

One obvious answer to time restrictions for investing presents itself – passive investing. In some ways low-cost indexing is that perfect solution to the time-poor new parent.

But maybe in other ways it’s not, because, to borrow another GoT phrase “Winter is coming”. And I don’t just mean that that at some point, at a time unknown, there will be another downturn and crash. We know that, and I have nothing to really add to that conversation beyond acknowledging that the consensus is that it is coming sooner rather than later.

No, I’m not talking here about the market cycle in this traditional sense, but rather our expectations for the market’s returns as a whole. I mean that at some point we may have to stop expecting the 10% annualised long-term average returns from the public equities markets [3]. The pendulum’s arc may just becoming narrower.

The historical returns we look to for guidance were established at times of greater inefficiencies in the market, many of which have been competed away [4]. The benefits we get as consumers optimising technologies like Uber and Netflix ultimately can come at the cost of the investors of those companies, many of which are yet to post profit.

In that environment, will you be happy with just market returns? If you have found yourself on Strawman.com, the answer is probably not. You are, at core, an active investor.

Balance

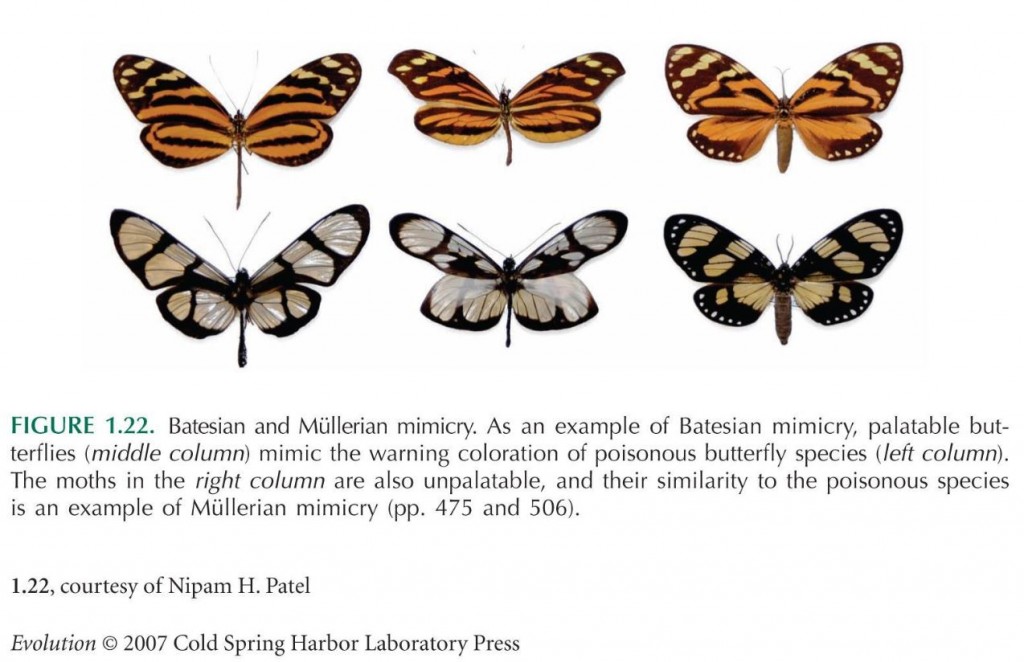

In my research of the classic ‘Active vs Passive’ debate the best analogy I have come across is that of ‘Batesinan mimicry’ [5][6]. Mimicry is the evolutionary phenomenon by which some less harmful species piggy-back off the dangerous reputations of other species. They may happen to share similar ‘warning patterns’ but not the actual defensive or attack mechanism – such as being the a bad-tasting butterfly or a poison dart spitting frog. The delicious butterfly and the disarmed frog (‘Mimics’) get a parasitic survivorship benefit just by looking like the real thing (‘Models’).

The Farnam Street blog post (linked above) applies the concept to distinguishing between active fund managers. However, for me the more appropriate analogy for it is that true out-performance is the Model which the passive investor can only ever hope to be the Mimic with market performance. Maybe the easiest way to think of this concept is to pretend they are like gang members. Your Model is your genuine dedicated thug with a street-smart edge. These guys have, they are, ‘Alpha’. Meeting them has consequences. Your Mimic rocks that gang’s colours, but they’re really not doing much more than that. Unfortunately Mimics are just a bit boring – and they’re not the ones sacking Rome and reaping out-sized bounty.

You know deep down that you want to be the Model, that dangerous one with the competitive edge. You want active investing and you want to do it yourself. You don’t want to pay your ‘protection dues’ to the likes of a modern day Chieftan Brennus and their ubiquitous 2 and 20 rackets [7].

What I found most fascinating about mimicry is the constant re-balance at play in nature in the population ratios of these types of species. Too many mimics and predators get wise to the false flag scam. Too many Models and scared predators create the environment for mimics to once again thrive.

At a certain point, on this back and forth ride of life, fortune favours one or the other. I think, for the first decades of my young family’s existence fortune will be more favourable to the Model. Ted Seides may have famously lost his bet with Warren Buffet on this issue, but the spectre that timing was a factor in this lingers [8]. Now could be time for nature’s true killers to show their fangs.

“Cool story Pablo, but is there any actual insight into the human experience here?” Another pertinent question from an even more patient reader.

As the unchallenged Apex Predator humans are history’s ultimate victors in the Circle of Life Hunger Games. What then is our edge?

Our big brains in our big heads. The reason our babies are born so helpless. And one of the reasons human pregnancies can be so dangerous for women without, or even with, the aid of modern medicine. The human advantage in evolution is our brain and our ability to consciously adapt to challenges, as opposed to just letting the eons do it for us by not allowing the weakest of our offspring to survive.

Adaptation

I have heard it said that if you are working too hard you are probably doing it wrong. Yes, to the victor will go the spoils but, as Morgan Housel has recently wrote, being the victor is not necessarily about hard work at all [9]. Tenacity will only ever get you so far unfortunately. The world is not fair. Both luck and innovation have a much greater role than any of us are generally comfortable acknowledging.

A most elegant example of this lies in a museum in Greenwich. Yes, of Greenwich Mean Time fame which we used to use before we just surrendered to ‘Apple Mean Time’ and let our iPhones tell us what the time is, and, if you are a Queenslander wake you up too early (or is that too late?) on the first day of daylight savings. The same devices which now allow us to pinpoint our precise location in the world on a GPS map at any given time.

Before we could take timekeeping and navigation for granted, there was the ‘Problem of Longitude’ [10]. Latitude was never such a big deal for us. Since ancient times experienced (but half-blinded) sailors could use the sun’s movement through the day to determine where they sat along the world’s north-south axis. The time of that day was the same in Rome as it was in Cape Town. Travelling east to west however, especially by sea, was fraught with more problems as numerous shipwrecks attested. Navigators could never be confident of their current local time relative to the time at their home port – the roll of the seas is brutal to clocks with swinging pendulums.

Then in 1714 the British Government established a Board of Longitude (by this part of the museum my wife was also Bored of Longitude). Prizes of up to £20,000 (over £2.6 million in today’s money) were offered. Early submissions included plans for humble sailors to track the movements of the stars, which basically required that they have a post-graduate degree in astronomy and lug around the associated equipment and charts.

Enter John Harrison, a reputable clock maker. For over 25 years he labored over three modified pendulum clocks, each more elaborate than the last. They were large clocks, about a metre tall and weighing between 30 to 40kg. None could past muster when put to the test.

The story is far more involved than I can do justice to here. And anyway, I had to stop reading the museum signs – the long-solved ‘Problem of Longitude’ had fast become a problem for my marriage.

So (spoiler alert), John Harrison’s fourth time-piece, the H4, solved the problem only after he underwent a significant re-think of his whole approach. As you can see it’s basically a watch. No pendulum. And it allowed those 18th century sailors to stop fretting about their HECS debts. This is a Model of human ingenuity at its best. Yeah, sometimes in life you’ve got to get off that tired merry-go-round, strip things down to the fundamentals, and stop caring about the back and forth of those big clocks. Simplicity is always the best destination, no matter how complicated the journey.

Perfection sometimes just arrives in the smallest of packages, and you rebalance things accordingly.

Right now, to the extent that I’m thinking about investing at all, Strawman.com is looking like one of the smartest and effective ways to research investing ideas as my idle hours dwindle. Time is precious, thank you for yours. I am striving for simplicity, but as you can tell, I’m not quite there yet.

Strawman is Australia’s premier online investment club. Join for free to access independent & actionable recommendations from proven private investors.

Disclaimer– The author may hold positions in the stocks mentioned in this publication, at the time of writing. The information contained in the publication and the links shared are general in nature and does not take into account your personal situation. You should consider whether the information is appropriate to your needs, and where appropriate, seek professional advice from a financial adviser. For errors that warrant correction please contact the editor at admin@strawman.com.

This Service provides general financial advice only, and has not taken your personal circumstances into account. Strawman Pty Ltd operates under AFSL 501223 . For more information please see our Terms of use. Please remember that share market investments can go up and down and that past performance is not necessarily indicative of future returns. Strawman Pty Ltd does not guarantee the performance of, or returns on any investment.

© 2019 Strawman Pty Ltd. All rights reserved.

| Privacy Policy | Terms of Service | Financial Services Guide |

ACN: 610 908 211 | Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL): 501223